Lately, I’ve become aware of this disturbing feeling I have that the most beautiful women I can think of are the women of the Netflix real estate reality series Selling Sunset. When I watch this show, I can feel how much I wish I were a person who could show up in a space looking undeniably fresh. I never look fresh. I love my clothes, and I aspire to a certain level of glamour, but I will always have this feeling that I am ultimately pretty dusty.

When I really scrutinize what it is about the ladies on Selling Sunset, aside from the gleam of botox and the fashion, that fills me with glitter-green envy, it’s that they always arrive at the poorly attended and horridly boring house party completely and totally properly coiffed: not a single hair out of place. And really, not a single one of them has curly hair.

What is this? Unhealed early-2000s hair trauma? Countless Supercuts haircuts where they’d spray my hair with water, comb it straight and blunt-cut it only for it to dry into a frizzy lopsided mane?

In a euro-centric culture, for so many complex reasons rooted in racism and xenophobia which we’ll delve into in future newsletters, straight hair has always been read as more “presentable.” The chemical straightening trend of the early 2000s, the hot-comb so-called professional “imperative,” the rise of the Dry Bar franchise. I need a thousand hours of therapy to understand why my brain still places these women as the standard of beauty. But it’s really not so surprising, is it?

It wasn’t until relatively recently, through powerful legislation like the CROWN Act, that natural and curly hair textures have become more celebrated, nay accepted. Curly hair has been increasingly embraced by the curly-haired themselves. Salons now offer curly cuts and dry cuts, cuts that honor the ways and whims of the curl.

So why can’t I unlearn that my curly hair just isn’t considered polished?

The answer, as you might expect, might be witches.

The “Unruly” Hair of Witches

Hair achieves literal unruliness in a multitude of forms, and in that unruliness itself often conveys a sense of marginalized identity. Margin-dwellers, those who live on the outskirts of towns and villages, those who dwell at the edge of the forest, mark those whose identities, whose narratives, are felt by the dominant culture to exist tangentially to its major themes: a threat to the status quo.

Witches, of course, occupy such a spot in history. Literally, witches were identified in Heinrich Kramer & Jacob Sprenger’s Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches, 1486) as single, unattached women living on the edges or the outskirts of the town. Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger were two knights of the crusade—the king’s henchmen for rounding up witches, i.e. single women across Europe.

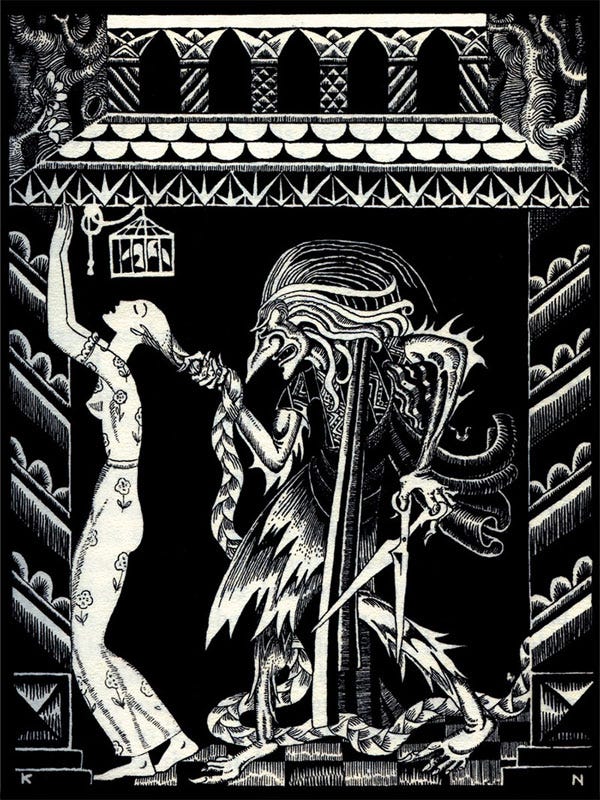

In their How-To text, they outline the special locale of the witch’s power as trapped within her long, unruly locks of wild, curly hair. Further, they warn, that if a witch shakes her hair at you, the hexes and spells she has cast upon you will double in their damning power, and consume you. Well, okay. Maybe we’re onto something.

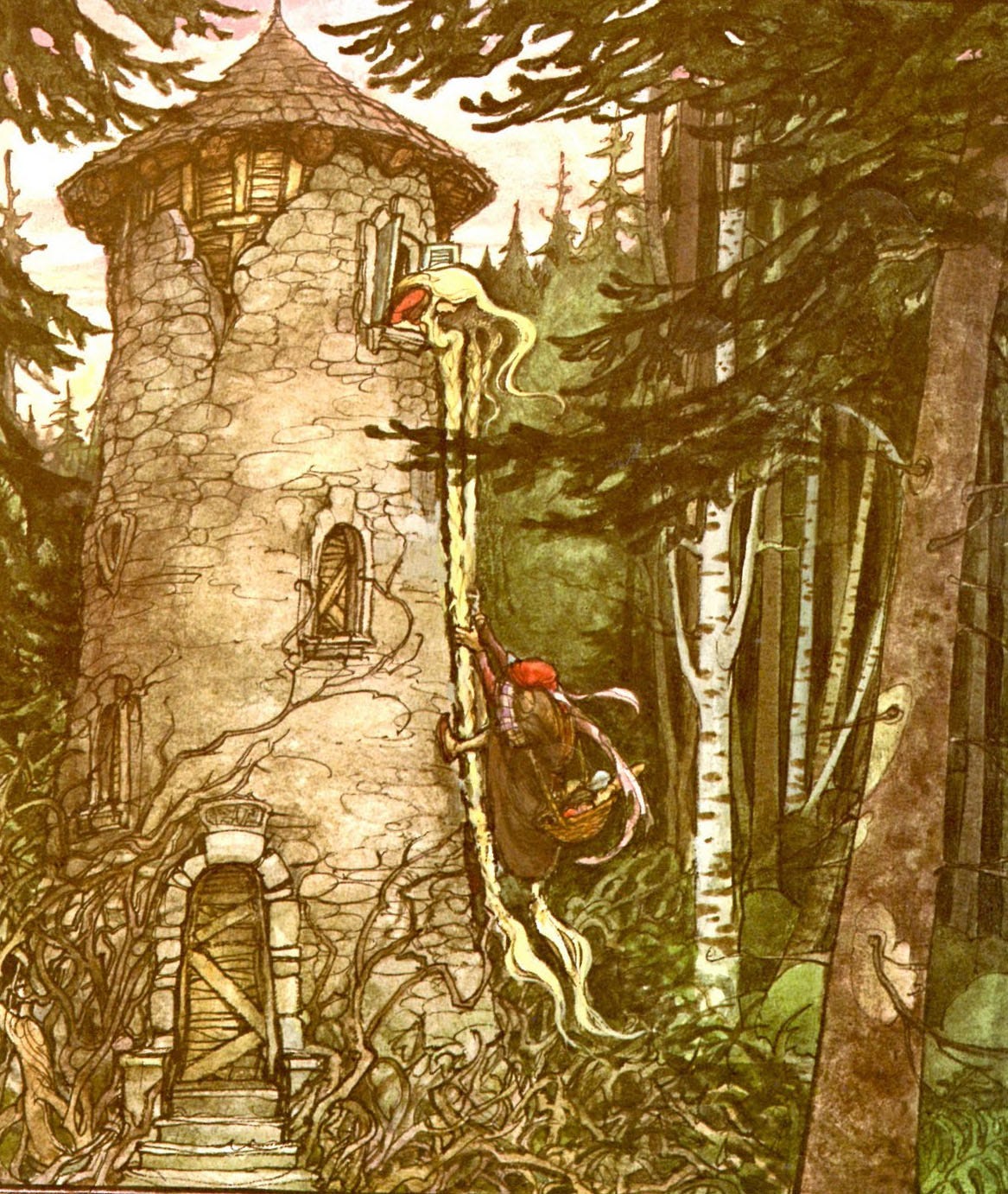

Many retellings of the fairy tale Rapunzel feature a tall tower and an ugly, jealous witch obsessed with youth and beauty. They feature a tall and handsome prince who falls in love with the golden-haired Rapunzel kept locked away in the tall tower with one window, no doors. In classic tellings of Rapunzel, the witch and Rapunzel herself are at odds: Rapunzel desires her freedom and the witch desires Rapunzel’s youth and beauty, and the social power that comes alongside those qualities. The narrative of hair and power is undeniable, no matter the retelling. So let’s unpack a bit how witches and hair and power have gotten so tangled up.

Witches are often portrayed with curly or messy hair or otherwise marked by “difference” in popular culture. Take, for example, the Sanderson sisters in the 90s classic Hocus Pocus (1993). Winifred Sanderson, played iconically by Bette Midler, has two massive mounds of curly red hair that curve like devil’s horns. Her sister Mary Sanderson, played by Kathy Najimi, has hair that looks like it got caught in the vacuum cleaner she uses as a broomstick. The youngest Sanderson, Sarah, played by the flighty Sarah Jessica Parker, has long and wavy blonde hair. The fact that her hair is down conveys her youthfulness.

In the Victorian imagination, hair occupied a place of power and sacredness. Hair left long and flowing would have been worn by young girls, signifying their health and especially their youth. When they became old enough to bear children of their own, their mothers would fasten their magnificent hair into the updos of the married and childbearing aged, signifying to local bachelors that they were ready to be married off. The Brothers Grimm, living in Europe during the Victorian era, would have been aware of the power and significance of hair as they retold the classic story of Rapunzel, after Giambattista Basile and Charlotte-Rose Caumont de La Force’s Petrosinella and Persinette, versions which predate the Brothers Grimm version of 1812.

Powerful hair arises in ever more witchy figures across popular culture. For example, the sea witch Tia Dalma, of the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, who debuts in the human form of Calypso (played by Naomie Harris) in Dead Man’s Chest (2006), has loc’d hair. While Caribbean spiritualities like Rastafarianism arose in the 1930s, much more recently than the 19th century pirates portrayed in the film’s franchise, loc’d hair would undoubtedly bear a cultural resonance and a spiritual significance to the African diaspora. Calypso has also been referred to as a mami wata figure, a siren, calling to sailors and demanding their undying love and fealty.

In 2006 when the film was made, the locs may have been a reference to spiritual beliefs of Rastafarianism. Rastafari take the Nazarite Vow to not cut their god-given hair, and therefore preserve their hair in the protective style of locs. Hair in this belief system contains the power of one’s own life force, and the protection and omnipotence of god. A reference to god’s power might underscore the power of the sea witch herself.

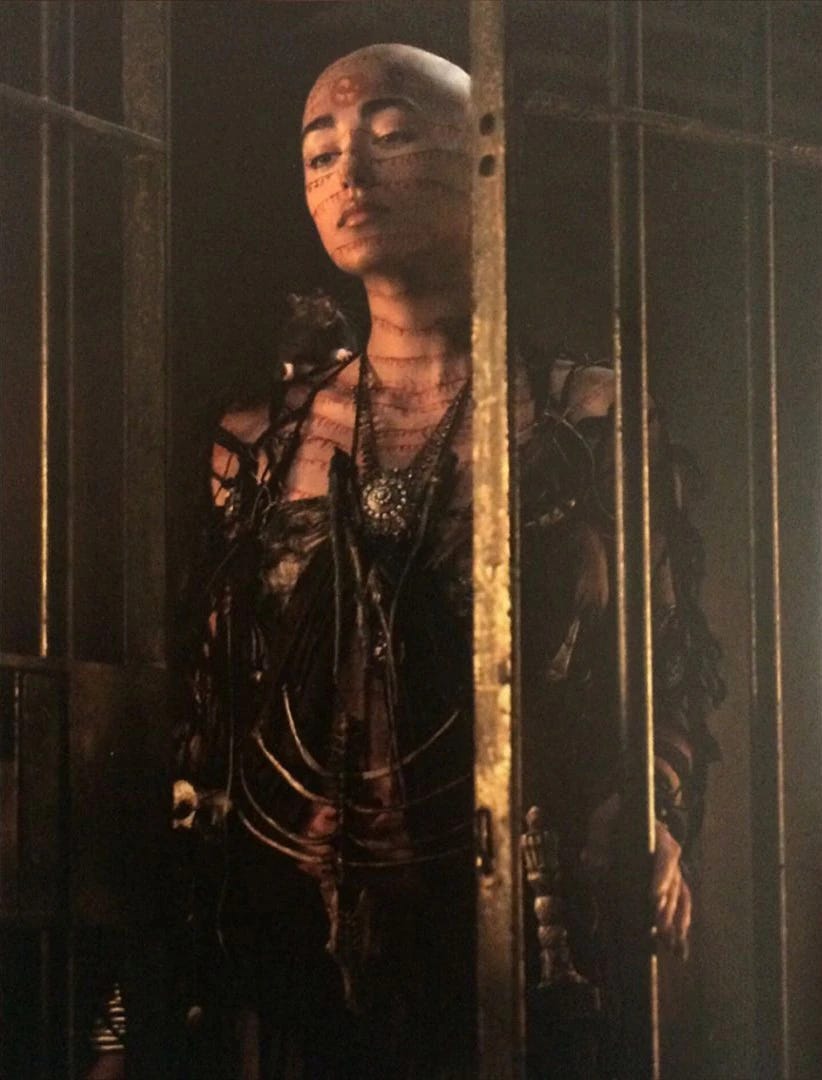

In 2017 another mystical femme figure also bearing a non-western identity entered the franchise. Shansa, a sea witch with a shaved head played by Iranian-French actor Golshifteh Farahani, shows up In Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017). Although we are used to white witches being portrayed with unruly, messy, often curly hair, it is interesting that two non-western witches in the Pirates franchise are furnished with powerful hair stories of their own, whether styled with locs, or a shaved head.

In many cultures around the world, a bald head may be a sign of tonsure, or ritual head shaving. Ritual tonsure is found in Christianity—when we see the bald-headed young priests with their halo of hair, we know that they have recently devoted their lives to the pursuit of divine worship. In India, ritual tonsure is a practice in many Hindu temples as a marker of coming-of-age. It is also how the temples make money, by ritually shaving devotees’ heads and conditioning the hair for the global hair market, where it makes its way into the highest-quality wigs and weaves. For Muslim men primarily, it is forbidden to shave one’s beard hair except for ritual purposes, at the start or end of a religious pilgrimage. We might view Shansa’s shaved head within the lens of the actor’s Persian heritage, and as evidence of the highly spiritual nature of the sea witch herself: her ongoing spiritual pilgrimage.

In each of these portrayals, the witches of non-western identities are portrayed with hair that references spiritual power, with special allusions to non-western spiritual traditions. These are still presented as marginalized hairstyles—hairstyles that evoke difference, or choice. And the hair, or absence of hair, directly references the witches’ symbolic powers.

The disintegration of the self in real life is usually symbolic, metaphoric perhaps of a splintering of the physical surroundings that an individual identifies themselves with. “My world is falling apart,” or “I split into a thousand pieces.” In fairy tales, however, it is possible to make the symbolic literal. The story of Rapunzel (in any retelling) might in fact showcase a splintering of the witch’s own identity such that Rapunzel and her hair become symbolic of the witch’s power itself, through the trauma of being systemically and historically hunted by figures like Kramer and Sprenger, witch-hunters.

Rapunzel’s witch is portrayed as obsessed with the power of Rapunzel’s hair to restore her youth and beauty. She is portrayed as jealous and ugly, as society sees her: a witch, an old crone. As we know, in The Hammer of Witches (1486), Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger identify the locus of a witch’s power to be her unruly tangle of long, messy hair. It is possible that the constant threat of persecution and death—for the text itself warns “thou shall not suffer that witch to live!”—caused the witch to create a talisman outside of her physical body to contain that power. In this way, we might understand Rapunzel as the witch’s power personified.

In the witch’s domain, hair itself is not only symbolic of a witch’s power, but it is seen as a powerful symbol of youth and beauty—perhaps further, a witch’s true nature suppressed by the encroaching blanket of Christian morality propagated by the hetero-patriarchy. If we understand Rapunzel to stand in for the witch’s power personified, then the tower is symbolic of that repression of self the witch is forced into; to updo her youth, her beauty, her potency in the figure of Rapunzel and, most notably, her hair, by relegating it and her to a tall inescapable tower.

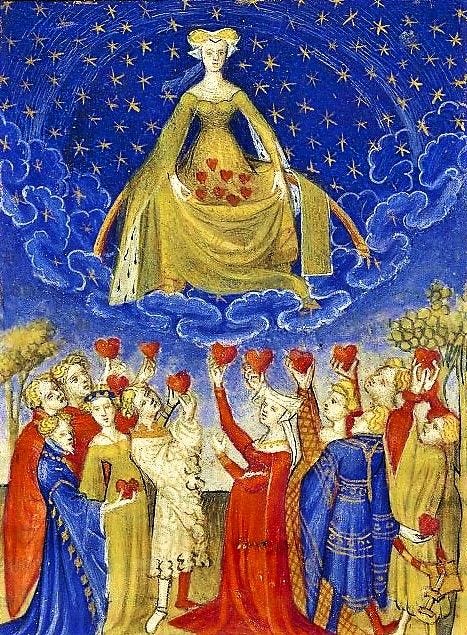

One of my favorite substacks,

, recently wrote an essay on the impressive (and complex) figure of Christine de Pizan, an Italian-born French noblewoman and intellectual of the 15th century, who is widely regarded to be one of the first published feminists. The essay contains lots of great information about her life, with gorgeous illuminations (medieval illustrations) from her published works.There is also a great passage in the essay on Medusa, yet another of HAIR CLUB’s mythical icons, where Christine de Pizan offers an alternate read on the stunning power of Medusa’s beauty, mentioning in particular her “long and curly blonde hair spun like gold…” which, as we all know, was metaphorically cast as a tangle of ugly snakes with the damning power to turn men to stone.

Christine de Pizan’s most famous work was a treatise on the innate power, capacity, and intellect of women called The Book of the City of Ladies (1405). The more I delve into research on Rapunzel, the more Christine de Pizan’s text seems to arise. Some scholars liken the witch’s tower in Rapunzel to Christine de Pizan’s utopian windowless city built to contain and protect women from their male counterparts. Obviously, I like this idea very much. If we can leap to understand the figure of Rapunzel, with her long flowing hair, as symbolic of the witch’s own power, then perhaps we can imagine the witch from within this proto-feminist lens building a tall tower to contain that symbolic feminine power and protect it from the encroachment of powerful censoring forces that wish to squash it out (i.e. the crusading church) or exploit it.

When does your hair feel “unruly”?

Throughout popular culture, unruly hair is often used to portray the over-sexed. Julia Roberts’ seminal role in Pretty Woman (1990) has her sporting the all-out 80s frizzed out curly mane that Flashdance (1983) made so popular.

Two women occupying roles that are slightly threatening to men: an empowered sex worker and a machinist. Edge-dwelling women with curly hair challenging the status quo. In fact, it isn’t until silver-foxed Richard Gere has her as a kept woman in his hotel room that her hair starts to transform: loose and wavy curls are tamed into “respectable” up-dos, or hidden under conservative little hats.

As I think about these movies, I find myself wishing the witch from Rapunzel would come swooping in and take them to the safety of her tower of powerful women, where they could all live undisturbed and unbothered, moisturized, in their lane, and happy forever after.

It's kind of understood that Delilah is a dangerous woman because she is independent and particularly because she's not identified by a relationship with a man (no one's wife or daughter), but exists in her own right. In movie portrayals, she's always got wavy or curly hair. Very witch on the edge of town vibes.

Not to totally uphold Christian mythology, but Samson’s powerful hair and Delilah’s frequent depiction as an unruly-haired person.