Whether we think of it this way or not, hair is line, form, and shape. Hair is content, event, and performance. Hair itself is mindless art—that is, it grows according to the wisdom of the body and not the mind, although we know events that affect the mind often affect the body, wise or not.

Many people, most people, have elaborate ways of caring for and preparing their hair to greet the public, whether that happens each week, each month, each day. We perform hair in countless ways, individual to each person. Sometimes, the act of hair care is an invisible dance of cascading veils designed to cover traces of care at all: to appear coiffed and perfected is akin to godliness. See: celebrity culture. See: the real estate mavens of Selling Sunset. See: hours spent in the salon chair to achieve the perfect look.

Like good design, hair often bows to the pressure to appear “effortless.”

Loving Hair Loving Care

The work of artist Janine Antoni playfully and poignantly questions traditional forms of labor, twisting the basic functioning of our bodies into productive systems that engineer perfect forms, or, art.

Far from using a judiciously-flecked paintbrush to move oil paint across a canvas, Antoni employs forms of under-explored bodily labor in her work: teeth for biting, tongue for licking, hands not for traditional sculpting but for washing away and lathering. Forms of labor we might consider as more innate conditions of living—the need to bite, chew, lick, wash.

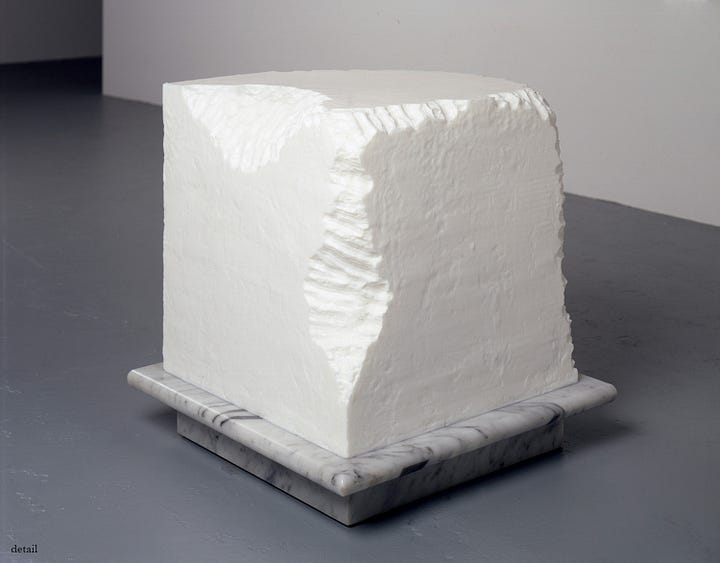

Her pieces Gnaw (1992) and Lick and Lather (1993) are some of my favorite works of hers. In Gnaw, Antoni created sculptures from large blocks of chocolate and lard, using her mouth to manipulate the material. If you look closely, you can see the teeth marks used as complete gestures across the blocks of chocolate and lard upon their low marble pedestals. Teeth become chisel, working away at the soft material.

For Lick and Lather, Antoni poured moulds of her own portrait bust in soap and chocolate, respectively. She made multiples of each. For the chocolate busts, she licked and nibbled on the sculptures, altering her own visage subtly by delicious attrition. She approached the soap sculptures in a similar fashion, with wet hands, lathering and smoothing the surfaces away until the forms were altered, or at least had lost some of their most defining features.

I like these pieces because there is something of the body in them, more purely and more cleanly than in the way a body transforms material into art in the traditional sense. Rather than making, Antoni’s labor in these works was to lick down, to wash away. Her work achieves special resonance when it engages the body as performance.

In Janine Antoni’s hair performance Loving Care (1993), the artist soaked her long hair in Loving Care brand hair dye, Natural Black, and painted the gallery floor using her own hair as the brush until the entire space was covered in large swirls of black dye.

From her website:

“The artist’s actions conjured up the expressive marks of Abstract Expressionist painting, linking them to the chore of mopping. As she claimed the space, the audience was slowly backed out of the gallery.”

There is so much to unpack here, from the act of mopping to the association with Abstract Expressionist painting. It’s important that these references come directly from the artist herself.

Abstract Expressionism is a post-World War II art phenomenon in the United States where artists confronted a crisis in representation after having lived through two world wars.

AbEx paintings, it might be said, are paintings of movement, motion, chance, gravity, and decisive action. Paint was flung, dripped, splattered, seeped, smeared, applied, and otherwise hurled onto the canvas with an expressive force that served to convey if not the visual reality of the time—as a still life or landscape painting might—then the emotional reality. The turmoil roiling beneath the surface of an otherwise polished 1950s pomade-slicked “American Dream.” The best of the AbEx artists sought to formalize, capture, and repeat, systematize what many saw as mere violent machismo flung at the canvas. Artists like Lee Krasner, Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell, Alma Thomas and Richard Mayhew saw in abstraction the opportunity to render an internal, emotional landscape, making internality and feeling an important subject of art.

In so many ways artists are the sensors of society, feeling the outward edges of what is true and transmitting that truth through their art.

Artists are like hair in that way.

And yet, AbEx still relied on the use of traditional tools and traditional modes of expression: canvas, paint, paintbrush, body. Collaborations with time and gravity, and the viscosity of the pigments are all at play.

The artist’s wingspan is a node I often focus on with my students: can you look at an AbEx painting and sense how tall the artist was, standing before the giant canvas? How far their reach extended? Can you imagine the flicks of the brush itself by looking at the length and width of each stroke? Can you inhabit the action of the painting?

Not the smooth blueing of a distant horizon or the careful gloss of disappearing brushstrokes we might find (or not find) in Renaissance paintings, for example. Instead, the path of the brush in abstract art of this period is often visible. As nearly accurate as calculating the orbit of a planet from the relative observed velocity of its passage through the night sky, one might look at an AbEx painting and say, by examining the radius of the splatter, the slow pool of the paint, or the drag of dry brush across the canvas how fast, or slow the artist’s hand, how much force was used, or perhaps even the distance from which the painter was flicking the brush, pail, or handful of paint in question.

In Janine Antoni’s piece, the artist’s hair becomes the paintbrush. Her whole body is involved in the act of mark making, kneeling prostrate on the floor with her hair flung out ahead of her.

In documentation of this performance, a big bucket filled with hair dye sits behind her and we watch the artist dunking her head in there repeatedly to re-moisten her locks. In the swiveling swirl of black dye on the floor we can see the full reach of her physical body, swishing this way and that in long coils. The artist’s own torso is the limit of her expressive mark-making, the split ends of her hair the flick and flourish of the bristle. We can imagine this by examining the path of “Natural Black” pigment across the gallery floor. The map of her movement shown in the wide swings of her hair and the tight, laborious pivots where her knees shuffled her ever backward. Smaller marks made by her fingerprints showcase the way she pushed herself across the space.

The most important detail of this performance, to me, is not the laborious effort of the body we might imagine in the strokes across the floor, nor the smearing hand prints that punctuate that labor in great gooey shoves of dye. It’s not the length of this durational performance, nor the documentation of it, nor the color of the dye itself, although those are all aspects of the artist’s myriad choices we might look to to generate a complete interpretation of the art piece.

To me, the most fascinating aspect of this performance, titled Loving Care after the brand of hair dye used to create it, is that as the artist performed the piece, and the artist “claimed the space, the audience was slowly backed out of the gallery.”

In other words, in order to complete the work: the audience must disappear.

So often we talk about hair as a performance, and the performance of hair itself, of simply having it, and the choices we make whether culturally- or familiarly- or texturally-determined around our hair. These conditions determine length, style, cut, shape, done up, let down, braided, pinned back, covered, etc. etc. These choices determine how our hair is read by others, and how it feels to be ourselves.

In this hair performance, Janine Antoni slowly forces the audience out. She takes a space that exists for the public enjoyment of art—the gallery—and she forces everyone to leave.

True loving care may sometimes be about making space, claiming space for oneself. As Antoni claims the space with her hair, she renders it un-perceivable.

I think that’s really fucking powerful.

In Suz news ::

This morning, I plopped my nine month old and her bottle in the travel crib we use as a pack n’ play and ran upstairs to do some hasty hair maintenance.

As I plucked my eyebrows back to a shape that made me feel better about my whole face, I took note: I’m making space for this. Most hair rituals requires gently forcing people out, carving a slice of precious time to confront your own body.

Since we had the baby, my partner and I often need to ask for this time from each other. This time, I was taking it from Arlo herself. I finished up and went to retrieve her from her little pen so we could resume her bottle time on the couch while I read next to her as usual.

How do you make time for your hair?

Does hair time intrude on other obligations or commitments? How do you ask for it? Do you simply take it? Have you tried painting the floor someone else is standing in with your own hair as a way of saying “hey, I need some time alone with my hair”?

xo, with love

A fascinating read as always. 😊

Thank you for introducing me to Janine Antoni’s work. I’m astonished at how much I can feel and sense each piece just through the phone screen. The busts especially have me thinking about times when my hair has been styled professionally, curled, blown-out, braided; no matter how well it’s done I always have an immediate desire to fuck it up a bit so that my hair feels like mine again.