Thresholds

Hair rituals as an act of passing through

First, a big warm welcome to all the newcomers in this space ! Thank you for the outpouring of support around Heavy is the Crown and also for sharing your hair stories with me in the comments last week. I don’t take them lightly at all. I feel so touched, overwhelmed and excited to keep digging into this ground together.

In HAIR CLUB, hair stories are incredibly important to our collective understanding of hair. Always, you are the expert on your own hair experience and I hope you’ll keep sharing that with us.

Many of you have shared stories over the past couple of weeks in which hair contains a dichotomy. After all, hair can hold many truths at once. This week, I’m thinking about the metaphoric potency of a hair ritual: how many threads of meaning can an act of hair removal unravel?

I’m so glad you’re here.

Hair Passages : Thresholds, Doorways, New Beginnings

We know hair marks time passing: it grows. We cut it. It changes with our internal weather. Breakups come for it. Grief and loss find us tearing at it. Stress scares it away.

A first haircut is an important rite of passage. The gloss of the plastic turtle chair; the feel-sound of the snip. Your hair wet in the mirror.

As I finished up my time at Wassaic Project this past week, I was grateful for the opportunity to host a Hair Salon event. In HAIR CLUB, Hair Salons are swirling conversation events that delve into the topic of hair in an expansive-associative dialogue, championing the anecdotal, and always uniquely unibrow—our definition of content that is inclusive of low/no-brow to high-brow reference and everything in between: unibrow !

After the event, as we shoved our glasses together at the local bar, one of the artists said: “I never fully realized how hair can be an organizing principle for important moments in our lives, our most potent memories.”

I loved the way he phrased that: hair as organizing principle for memory.

One particular memory that came out of this magical hair conversation, a story told by one of the other artists in residence, has been sitting at the top of my mind.

It’s a short story, but it contains lots of time, and condensed emotional weight.

During the pandemic, the hair on my head and in my beard went silvery gray, then white.

“From stress?” I asked.

They nodded.

Post-pandemic, however, my hair has slowly returned to the way it was before: dark and sort of black-brown.

I had never heard of hair naturally returning to a former state. Listening to this artist’s story I was shocked and deeply moved to think of hair returning to an earlier state. To think of hair “healing” itself. I was familiar with the concept that hair could be a measure of our mental health, a visual register of our nervous system. But it had never occurred to me that a hair passage could actually be reversed.

On a trip to Niagara Falls in middle school, we stood at the precipice of the falls as the water rushed to meet itself below. Later on, we were handed plastic ponchos and passed through the metal turnstiles to get onto the ferry boat. We bobbed out to where the water churned in on itself in a deafening rush. Water flecked our ponchos and the glasses of the kid next to me and it felt like every story about the falls was told from the land of “what if.” What if you went over the Falls? What if you went over the Falls on purpose? What if you went over the Falls by accident? What if you fell?

At a local museum we learned about a black cat that went over the Falls in a bucket. The story is that it came out of the ordeal alive, but its fur turned stark white from fear.

I used to think that this story about the cat was as common knowledge as some scripture. I would reference it casually in conversation. “Like that cat that went over Niagara Falls.” Meaning, you get frightened and you sustain great physical change: inward signals outward.

I often visualize hair events as happening in one direction—the direction of time. While hair “can always grow back” (a comforting refrain told by good friends to the victims of bad haircuts), I tend to think of hair changes as doorways we pass through in a never-ending surrealist hallway. Time moves forward; so does our hair.

Even when I cut my hair back to bangs last year I could never quite get them to look like the bangs I’d had in previous periods of my life. They even felt different. A hair return is more like a distorted reprise: an echo of the familiar theme, but newly syncopated perhaps with the rhythm of what we now know. Same, but with new resonance.

When I found out Heavy is the Crown was featured on Substack Reads last week—making Pull out your own Hair a 2023 Substack Featured Publication (!!)—I immediately hopped in the shower and shaved my legs.

At first, it felt like a joke. What was I doing?? Shaving my legs that day hadn’t been on the agenda. And really at first glance it felt like an old habit: to be visible (even digitally! even through the screen!), does my hair have to be invisible?

As I was performing this ritual, however, I came into an awareness that I was shaving not to perform my body for an external audience, not to prepare myself for the world outside—as I had previously used this ritual to do—but this time to mark an internal shift. In a lifetime of performing this act of hair removal as rote and imperative, I had felt moved to use the ritual to mark a passing: from one moment into the next—as a way of celebrating, of preparing—as new community flowed into this space.

And really, it felt like a threshold. As I returned myself to a hairless state, I privately marked the turning of a page.

I think I’ve mentioned before how during the pandemic, when I stopped having to perform my body as hairless thanks in part to Zoom’s blur feature while remote teaching, I began to explore my natural hair removal rhythms from outside of that pressure to perform. When did I feel like shaving my legs? Or plucking my eyebrows and face? In the absence of the ability to go out and get a haircut—the most obvious of public-facing hair upkeep rituals—I turned my attention inward and softly monitored the surface of my body.

It got me thinking about the ways we prepare for whatever’s next through our hair rituals. In many ways—and paradoxical perhaps to biology—removing hair makes me feel more armored.

Over the past two weeks at my artist residency in upstate NY, I used the time and space to go on a hair journey. I decided at the beginning that I would simply stop maintaining the hair on my face. Eyebrows of course, but also the hair that grows on my neck and chin.

It wasn’t easy. I’ve worked my entire life to be and stay as hairless as possible, to remove “unsightly” hairs as soon as they crop up. In the context of this professional opportunity, I felt torn between wanting to perform the “best” (most polished) version of myself and wanting to feel authentically rooted in discovery through hair.

But then in the middle of my residency, death happened; I found out that someone in my family had passed away. In the soup of grief and reflection that follows this type of news, I thought: oh no, I’m going to have to pluck my chin.

It wasn’t until I was standing in front of the mirror I had found in an empty room upstairs and dragged into the brightest room of the old house we were staying in to catch the best light for plucking that I remembered: pulling hair is itself a grief ritual.

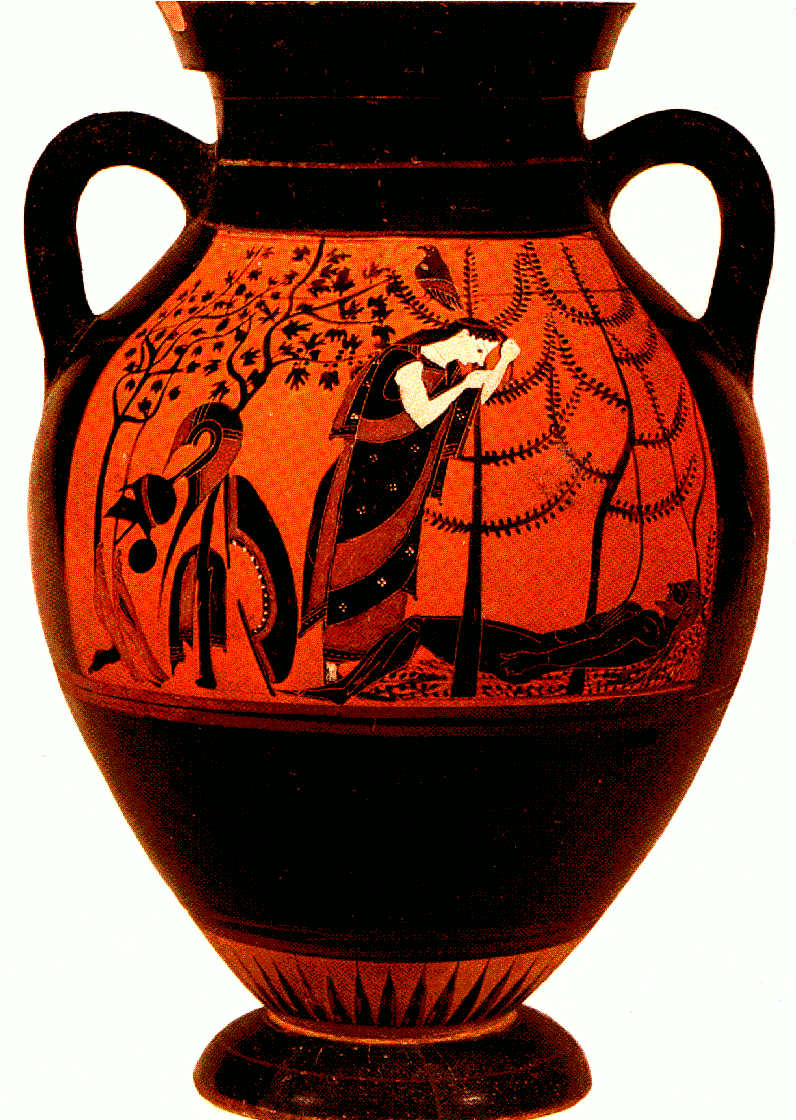

In certain regions of ancient Greece, a funerary practice emerged in the 8th century BCE wherein professional mourners would gather outside the home of the deceased to sing mournful songs and beat their chests. The chief mourners (usually spouses, sometimes a child or siblings) would ritually tear at their hair and clothes in mourning. These rituals marked the passing of a soul into the afterlife, and were most often performed by women.

Ritually and communally pulling at one’s hair in grief finds many depictions in Greek vessel painting. In some regions, it was also believed that in order to find safe passage into the afterlife, the deceased would need ceremonial offerings, graveside libations, and hair clippings of their closest relatives to guide them onward, passing from this world into the next.

What at first had felt like a moment of social pressure to appear hairless and “presentable” to the rest of my family at the funeral the next day quickly became a ritual of preparation, of sitting in the muck of unexpected loss and ruminating on it.

As I stood in front of the mirror that morning contemplating my chin, the morning light poured in generously, gold and glistening as the sun rose. I kept furiously plucking, scanning my face for errant hairs.

As I plucked, I gathered the fallen hairs and dropped them into a tiny jar I had brought in case I wanted to mark the passage of time by collecting my own hair in it.

I often want to forget I have a body—being perceived is complicated. But maybe I’ve fallen into a new pattern. Maybe I am moved now to remove hair as more of a ceremonial threshold, as an act of passing from one phase to the next.

In the end, I was glad to couch the instinct to return my face to its usual armored hairlessness as a grief ritual. To give meaning to the act beyond just doing it.

Ultimately, it felt like growth.

xo as I emerge from the woods and re-enter the world !

Really interesting reading. I enjoy not only your present thoughts regarding the growth, re-growth , colour and changes which which might take place with our hair according to our our experiences, but the historical context too.

Kind regards Ruth

The surrealist art in this newsletter rules. The one of the girls in the hallway with the sunflower I am obsessed with now! I appreciate this deeper consideration of hair. There’s a cool witchy lady on YouTube who does hair braiding magic, have you seen her? She’s called Journey of a Braid