I should begin by telling you I’m growing my hair out. This is essential context. And anyone who has ever tried to grow their hair long can attest: the agony of the in-between, the ‘awkward stage,’ cannot be overstated.

I am on what in HAIR CLUB we call a Hair Journey.

The Hair Journey, which can be big change or small in scale, epic or the tiniest shift in hair ritual, is a classic HAIR CLUB experiment in embodiment. When we teach our curriculum, “HAIR! HAIR! HAIR!,” in graduate and undergraduate programs internationally, we usually assign a hair journey as part of the coursework.

In the classroom, we task our students to take on embodiment as a central theme of their study of hair. As they do their thoughtful research into a hair topic of their choosing, they must also undergo a hair journey of some kind for the duration of the class, and write about it. Some will decide to stop shaving their armpits or legs, while others will dye their hair blue and document how those around them react. Much of the reflection centers around how it feels to be perceived in a new way through a simple hair change.

Once, we had a student shave their long hair, hair that had been fetishized for years by their parents, hair that they had never cut themselves. Their journey was a short and violent one: they took on the assignment in the form of performance art, inviting spectators to gather and cut a length of their hair, any length, with scissors, and then buzz off sections once it was short enough, until their head was completely shaved.

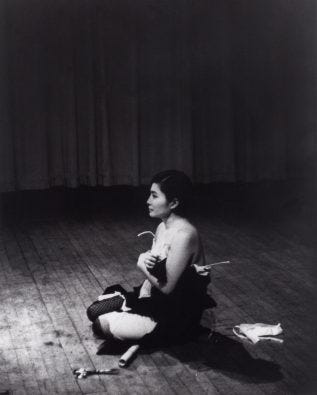

The performance achieved all the poignancy and vulnerability of Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece of 1964/5: a performance in which the artist sat on a stage with scissors in front of her and allowed strangers to cut off sections of her clothing until she felt the piece come to a natural end. From MoMA’s website:

The audience had been instructed that they could take turns approaching her and use the scissors to cut off a small piece of her clothing, which was theirs to keep. Some people approached hesitantly, cutting a small square of fabric from her sleeve or the hem of her skirt. Others came boldly, snipping away the front of her blouse or the straps of her bra. Ono remained motionless and expressionless throughout…

In this performance, the spectator becomes implicated, yes, invited to engage with the artist in such a deeply personal way, but ultimately it is an act of violence to have your protective layers cut away from your body, especially a marginalized body. Ono considers these pieces to be like a musical score: a set of instructions that must be interpreted, and may mark a different pathway or outcome for the duration of each performance. “We usually give something with a purpose,” Yoko Ono said, reflecting back on the performance years later. “But I wanted to see what they would take.”

In the context of our student’s performance, it was powerful and honestly devastating to watch as they impassively endured being shorn in this way, with no control, at the whim of others. I cried while watching, and as much as I wanted to support them by participating, I could not bring myself to touch their hair. I watched as others gleefully participated, laughing as the hair fell away in a blanket around the performer’s body. They sat resolute, spine like a column of stone, face impassive, but tears streaming down their cheeks. I wondered how anyone could feel so free with another person’s matter: hair is dead but its power is undeniable.

Afterwards, in their own reflection of their Hair Journey, they reported that an exhilarating calm fell over them, as though they had been released from all the burdens and obligations they had once carried in their long hair. I thought: how beautiful.

In the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, Roman noblewomen would have their portraits carved in elegant marble busts. While some emperors commissioned idealized portraits of themselves looking their best: young, virile, strong, gods-like. Others had their portraits carved in startling naturalism, the crags of old age all present and accounted for.

Perplexingly, it’s been found that occasional marble busts of Roman noblewomen are fashioned effectively bald, or with a subtle hair texture carved close to the dome of the scalp, with evidence that something else had once been affixed to the top. It is well known that Roman women favored wearing wigs, but could there have been portrait wigs? Wigs carved from marble to adorn the portraits themselves? In fact, many Roman portrait busts have been found with accompanying marble wigs to place on top of their portrait’s head, which could be switched out as needed or desired.

Some historians say these marble wigs, carved specifically for certain portrait busts, were commissioned to more easily keep up with changing hair fashions, and to save on the expense of entirely new busts as the women grew older. Hair fashions tended to change with the passing of one empress to the next. But this scholarship has since been debunked as a misogynist desire to frame women of this century as vain and more fickle toward their hairstyles than they really were: the assumption until recently was that women were consumed by an obsession with their outward appearance, hair included.1

The interchange of marble wigs on Roman statuary more likely has to do with testing out carving techniques for different hairstyles and textures, as they changed on a more empire-wide scale, rather than on an individual scale. In fact, some Roman statuary exists as the best evidence that Roman women of the 1st and 2nd centuries wore wigs recreationally, as with the portraits of Empress Julia Domna, second wife of the emperor Septimus Severus.

Whatever the reason for these marble wigs, I like to think of it this way: to have a closet in your house, or domus, a shelf of carved marble wigs of all the hairstyles you sported over your entire life. What a dream. What story would that shelf tell? Tales of your youth? Of regret? Breakup haircuts? When you thought you could pull off the Flock of Seagulls in the 80s?

I recently sculpted for myself a portrait bust in the classical style out of paper clay, and have been creating sculpted wigs of all my more iconic hairstyles in my lifetime to place upon it. I’m interested in the narrative potential of hair: to tell a story of my own maturation through my hairstyles, each one a journey of realization.

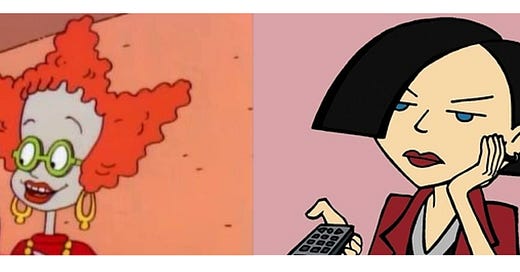

Even if the shape of my hair right now isn’t quite right—I am deep in the Awkward Stage—it’s always a hair journey. Always in flux. In grad school I worked long and hard for the Didi Pickles from Rugrats: flat-bottomed and wide triangle shaped (maybe without the top triangle). I really did visualize this for nearly two years! Once I achieved that, graduated and moved back to Baltimore, I wanted something different. I grew out my bangs and found Jane Lane from Daria—side-parted and still flat-bottomed—rocked that for a while.

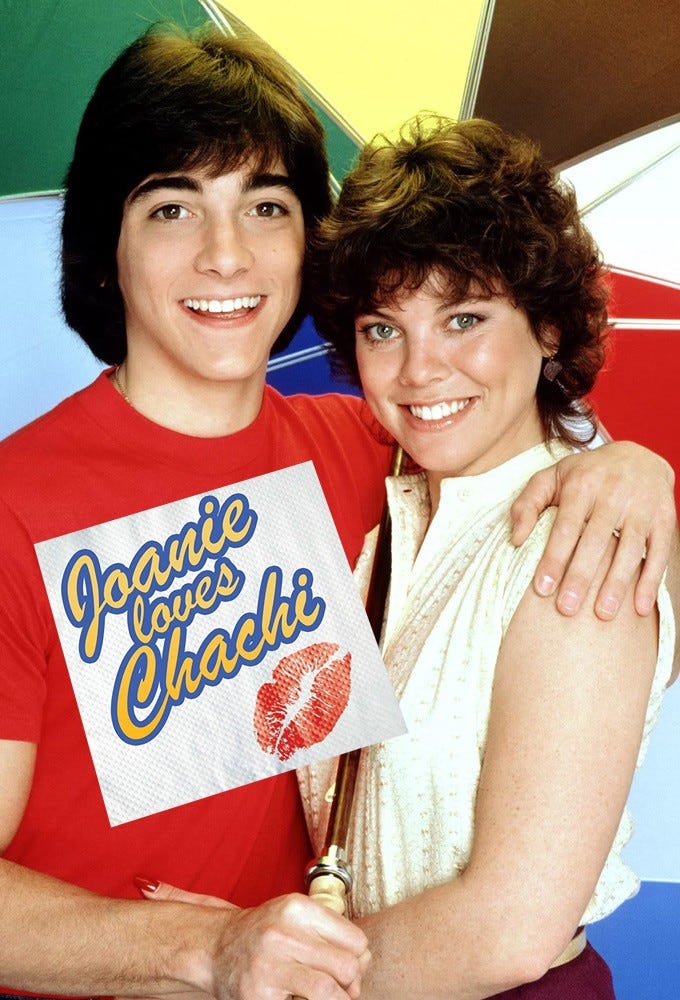

Now, I’m growing my hair long again, and keeping the bangs, something I’ve always wanted to try. Right now, I’m hovering more in the range of Joanie and Chachi, a personal fear of mine.

We’ll see if I make it.

As I continue writing from this body—something I NEVER thought I’d do—I feel like I’m tracing the contours of my being in new and strange ways. I have spent much of my life avoiding really looking at myself. Continually examining my hair keeps placing me in context with the physical edges of my body in a way that makes me suddenly more aware of the real space I take up, as opposed to the energetic space of my floating brain. Hair after all marks the boundary line: the contour drawing of my body from any angle would be done in hairs, both tiny and long.

Soft sensing hairs make the wind a ripple, help to regulate my temperature by standing on end, ensure the future growth of thicker hair to protect me from colder temperatures. Long hairs float in the breeze, more perceived than perception, become “Suzanne on a windy day” or “Suzanne dressed up for prom.”

Alongside this exploration of my edges, I come to a new understanding, or perhaps a more complicated understanding, of where I begin and end. I’m no closer to feeling how big I am in this world; the scale of things is constantly throwing me off. But I am starting to sense the wisdom of my own body, and growing more and more comfortable with the amount of energetic space I take up.

As I move between styles and lengths, I wonder: can transitions happen in sharp edges, in angles? Or is it always a soft ballooning into the right shape? Until my hair is the shape I want again, I won’t feel like myself, because every time I see myself reflected I do not recognize myself, that distance is felt in my bones as essential dissonance.

When my hair isn’t right, I’m not right with myself at all.

Sending love as summer glides in.

The Hair Journey

What type of Hair Journey are you on? Can you think of your most significant journey with your hair? What did you learn? How did it change your hair rituals? What does it mean to you to have a Bad Hair Day?

I’d love to hear from you.

Bartman, Elizabeth. “Hair and the Artifice of Roman Female Adornment.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 105, no. 1, 2001, pp. 1–25. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/507324. Accessed 1 June 2023.

Maintaining my short hair should mean getting it cut every few weeks rather than the every few months I manage to stretch into. The last month is always brutal: hating my reflection, feeling ugly and uninspired. Generally slumped. Eventually someone suggests my hair has grown long and I realize the solution to all of my problems is--aha!--a haircut.

I have to relearn this lesson every time.