This post is a bit too long for email format, so if you want to experience the full text, please read in a browser or on the @Substack app!

I have a new hair shape and I feel more firmly rooted, truly planted within myself, than I have in months.

On the day I got the haircut, I took my new hair out for a drink.

Texted a friend:

omw w new mullet !

Recently described to a friend that I haven’t been as concerned with how my hair looks lately, because of how solidly right it feels just sitting on my head. This was a gender-affirming cut and I feel very much like myself just wearing it. It’s hard to describe how much of a shift this was for me, but perhaps you’ve felt this way too?

I’ve been thinking lately about how hair plants us, roots us within ourselves and tethers us to our literal heritage. Hair showcases narrative at the level of the communal through shape, texture, length, but also perhaps even at the scale of an individual, single strand.

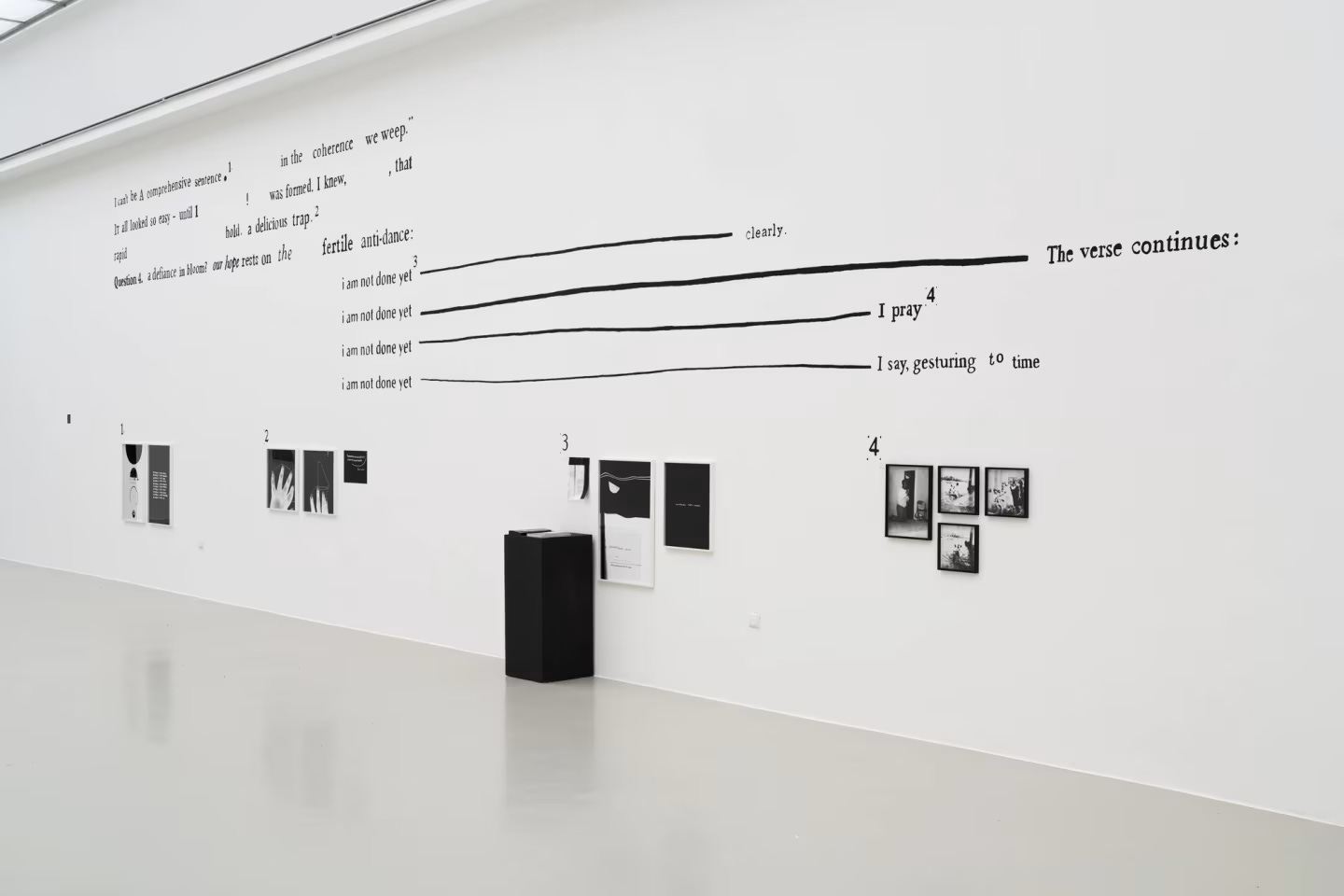

In the Art21 short documentary “Kameelah Janan Rasheed: The Edge of Legibility,” Rasheed, an artist who engages text and installation in her multi-faceted work, invites us to consider the contours of our experience encountering ideas.

She says of her own practice:

“It’s an invitation, come think with me.”

How do we think with a text? Here, ‘text’ broadly defined as any work of art.

Rasheed’s works, a combination of found and generated text evoking annotations, as well as prints, drawings, and installations that engage with thinking as an active, expansive, and often collaborative space derives in part from studying her father’s annotations of the Quran when he was converting to Islam during college. The notion that we can speak to, or speak back to, and think with, a text is, to me, probably the ideal way to engage with art.

What is the difference between thinking with something and thinking about something? One feels more collaborative, communal. The other, perhaps, more extractive, and even maybe invasive. The former implies a collapsing of the narrative space: ‘I think alongside this work, at the capacity of my own embodied understanding.’ The latter implies that I might be coming at the work from an opposing angle, standing apart from it. I prefer to inhabit. And thankfully, when discussing art that involves hair, it is always possible to inhabit the work.

This month, it’s an honor think with the multi-disciplinary work of Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum alongside you.

Where your own interpretation, your own experience, your own ideas diverge from mine, please enrich our space with your thinking in the comments below.

The Hair Work of Mona Hatoum

How is a sentence like a thread, like a strand of hair?

In my last newsletter, I shared this piece by Mona Hatoum called Keffieh (1993-99). It is comprised of human hair on cotton fabric and exists at a dimension of roughly 45x45 in. square. In this work, the traditional Palestinian keffieh pattern is woven with human hair in a tenuous and gentle gesture. It feels as though any thread of hair pulled might unravel the cloth. And yet, its tensile strength is evident in the line weight, the measured consistency of the locks themselves.

What would it be like to wear the hair of a loved one like a scarf? What would it signal beyond its pattern? What would I know and feel more deeply in wearing it?

The Keffiyeh pattern has had multiple symbolic resonances throughout history, but first and foremost it is a type of woven cloth, usually in a black and white pattern but also seen in red and green, that has become associated with the cause of Palestinian liberation. Worn throughout history by leaders of Hamas, some associate the cloth with anti-Zionist sentiment, that is: worn in defiance of the British occupation of historic Palestine. Members of the Palestinian diaspora, as well as non-Palestinians, wear the keffiyeh as a symbol of solidarity.

It is also worth noting that because of its associations with this anti-colonial movement, the west has sought at various times throughout history to cast the keffiyeh as a symbol of “terrorism” in an attempt to homogenize the narrative around what it means to fight for freedom.

A few weeks ago, I attended a lecture at the University of Maryland on the intersection of the movement for Palestinian Liberation and Black Radical Feminism during which the visiting scholar, who is of Palestinian heritage, was asked by a fellow academic whether she was worried about the destruction of Palestinian universities, museums and libraries.

“What of the loss of information, of records of your people? How will you continue your research?”

The scholar acknowledge the tragic loss of these documents and artifacts, and understood why a fellow academic would mourn that loss. “Fortunately,” she replied, “there are other ways to carry information across time than these western fortresses of information.”

My mind immediately fled to oral tradition, and then to fabric.

What is weaving? Woven thread? Throughout so many cultures, weaving literal strands of history into cloth has been a way of solidifying and planting the histories of a people into its lived visual culture.

According to Arab fashion historians, the distinct black designs on the white keffiyeh cloth symbolize ancient trade routes that came through the fertile lands of Palestine, the waves of the Mediterranean Sea, on whose shores Palestine used to sit, and the nets used to catch fish symbolize economic freedom and prosperity from the river to the sea.

As I sat in the audience at UMD and witnessed this resilient historian crack open the minds of her colleagues in the way she valued these non-western methods of transferring and preserving information, I thought about how remarkable it is that our bodies live to carry stories. Of course through memory and language and music and song and rhythm and movement and ritual and feast and gathering.

But also through hair.

In this work by Mona Hatoum, a Palestinian artist who was forced to flee to Lebanon after 1948, I can feel the interplay between the notion of transience—each thread a strand of hair that has fallen out—and also of solidarity, of cultural symbolism, identity firmly planted, and ordered within the fabric itself.

In a way, a bolt of cloth is a home for wayward threads. Cloth makes sense of what might otherwise become tangled, intangible, inscrutable. What wisdom woven fabric holds, what sacred internal logic.

I have been following along with the independent Palestinian fashion brand the nöl collective for many years. The work they do to help preserve ancient weaving techniques in Palestine, even through the ongoing occupation, is remarkable. These techniques have been passed down through machine and human hands generation over generation. Both through the garments and items they design and the access they provide to the weavers themselves, who are currently navigating unfathomable loss, nöl collective provides access to the ancient and precious wisdom of cloth and pattern in preserving Palestinian cultural heritage.

In the 200 days since October 7, the weavers’ workshops in Gaza that nöl collective works with to produce their garments have been irrevocably destroyed. Looms splintered and the buildings in ruins due to the unceasing bombings. Many members of these weaving families have been killed. Beyond the human loss, craftsmanship itself is under threat; the potential to continue these traditions, plant these stories in future generations cast into dangerous and tenuous scarcity.

Mona Hatoum’s gesture in Keffieh is that of re-planting. Taking the detritus of human existence—hair itself—and re-investing the cloth with the preciousness of that singular evidence of humanity. Fabric is understood historically as one of the earliest and most important technological innovations in human history—but to also have the threads themselves made of human-generated biological material invests the fabric with something even more symbolic, even more precious than even just the idea of history: the individual person, the people themselves.

I think it is a miracle that Mona Hatoum’s Keffieh, like so much weaving tradition in Palestine, seeks to unify warp and weft into such beautiful, meaningful designs. The act of weaving is necessarily an act of unification, of ordering. It is an ancient act, a site for storytelling and recording history, which makes it all the more poignant that Hatoum weaves hair through hers.

In a 1998 Bomb Magazine interview with artist Janine Antoni, Hatoum said:

Although I was born in Lebanon, my family is Palestinian. And like the majority of Palestinians who became exiles in Lebanon after 1948, they were never able to obtain Lebanese identity cards. It was one way of discouraging them from integrating into the Lebanese situation.1

The thread of Hatoum’s hair work is generally understood in the context of dislocation. Exile, refusal of state and legal status, something many Palestinians still struggle to achieve today in Israel and across the West Bank, within their own ancestral homelands.

Where is a person supposed to belong if not to their own ancestral lands?

Belonging, dislocation, root shock. Areas of disenfranchisement and displacement. These are stories hair is uniquely positioned to tell.

In Hatoum’s work hair is both the material substance of the work as well as its symbolic image. Often, a symbol becomes a stand-in, physically altered from the idea it comes to represent. Hair in Hatoum’s work may be read as its own signifier, and also as a scale model of the whole. A single strand as important as a cluster of multiple strands.

Hair is sticky in this way.

Sometimes an idea develops over a long period of time before it finds a “home,” so to speak. The hairballs that ended up in Recollection were collected over a period of six years.2

Hair is a fascinating material. Yes, it comes in individual units—a strand of hair—but it is also most often perceived in the gestalt: a whole image or shape. An entire head of hair.

Encountered individually, it is easier to separate from the human that made it, but collectively the strands unify into a single recognizable gesture: a lock, a ribbon, a clump, a head, no longer a strand but a braided chain. Even so, an individual strand becomes emblematic of a whole. And in terms of the relationship to narrative, history, and storytelling: there’s a literary term for this. When a single part references the whole, it’s called synecdoche.

In Hair Necklace (wood) (2013), Hatoum’s own hair has found a ‘home’ in these hair beads. A more general term for these might be ‘hairballs.’ Here converted from an item of disembodied hallway disgust to an object of physical beauty and value: jewelry which denotes royalty and ceremony, an occasion. This work situates hair as a precious commodity, precious bodily output. In fact, it took nearly six years to amass all of the hair it took to create this work.

The work also posits hair as a piece of armor donned to project a sense of power and beauty. That hair can be recast as a valuable and covetable necklace raises the value of that hair.

And really: isn’t our hair a sort of armor?

Hair Drawing (2003) represents a series of “drawings” Hatoum made wherein random clusterings of hair are affixed to handmade paper. In this example, a thicker cluster of hairs creates an almost perfect circle amidst the chaos of scattered curls.

I have been documenting my own hair on shower tile for nearly two decades. I’ve called them “hair drawings” too, long before I knew of Mona Hatoum’s work.

Seeing these hair drawings makes me feel held in a way that’s hard to describe. Her work feels so generous. This hair, offerings. The work administers a sort of care, even as it calls out systemic injustice.

In other works, for example, Interior/Exterior Landscape (2010), hair is used to represent the literal remnants of a life lived. Hair dangles from the bare bed frame on one side of the room installation “like cobwebs.” At the head of the bed, hair is suggestively left on the pillowcase, an “uncanny evocation” of humanness.3

What is a room’s relationship to freedom?

It is difficult not to think of incarceration in this piece. The spare quality of the room, more than adequate as a space to sleep or be, but not without an institutional feel. The scale of reference here is so important. To some this bedroom might seem uncomfortable, a cell, while to others, the notion of a room of one’s own is central to the idea of belonging. The luxury comes in the feeling of being planted in one spot, to have an uncontested home.

Across the room, a single hairball sits in a small wooden birdcage. The walls close in. Is a room a container for humanity? Or a cage? How far does one’s own interiority extend? And what remains?

Hatoum’s knotted hair grid sculptures are far more fleeting, almost impossibly delicate.

In Hair Grid with Knots (2001), the artist’s own hair is woven into a loose grid with single strands of hair knotted together. One long continuous thread of hair is looped and woven into itself with hairs trailing off at the top and the bottom looking oddly lost and wispy next to the logic of the grid.

At once ordered and also slightly haphazard, I can feel the tensile pressure of hair against hair, and the rigid pliability of each hair as it loops around to form a new row, or weft, of the grid.

As public-facing as hair often is, historians often read “intimacy” into hair, another of hair’s dichotomies. I’m beginning to understand that when people say “intimate” and “vulnerable,” what they really mean is: so personal that it achieves the universal. Hair too is personal yet universal. Repeatable, infinitely renewable, and relatively effortless.

We grow hair outside of desire.

The more I talk and write about hair the more I wonder if hair really is so intimate. Or is it society and culture that has coded hair as intimate? Of course in many religions a woman’s hair is a place associated with sensuality and desire. In many belief systems hair itself is sacred, perhaps related to hair’s natural propensity to grow: in Rastafarianism, for example, hair is god’s gift and should not be cut.

Society tells us that hair is intimate, a node of vulnerability. Really, hair is our body’s only natural armor. Hair is strength.

In Pull, a performance first conceived in 1995, Mona Hatoum’s own head is displayed upside down in a video mounted directly into the wall. Just below the smooth-mounted screen is a small niche in which hangs a thick braid of hair, tied off at the end with a hair tie. In this photo documentation of the work, a man tugs at the hanging hair while the artist’s face in the video above it makes a shocked expression. It looks as though he is tugging at her actual hair because of how the artist’s head is cut off slightly at the top (along the bottom of the screen frame). And in reality, he is.

Invasions of body and space. The way we intrude on the humanity of others and feel a false sense of ownership over their bodies, depriving them of their own physical autonomy. Pull exists to remind us that even though we may be able to see someone’s hair, it’s not for us. It’s not for us to reach out and touch, and if we genuinely feel the need to do so, we should examine ourselves.

Hair may be an intimate substance, and it is certainly very personal. Pull speaks in two ways of personal autonomy. Through the lens of Feminism, it reminds viewers of the necessary autonomy of women’s bodies. Through a post-colonial lens, it is a reminder of the necessity of a people’s right to autonomy, and an acknowledgment of one’s own basic humanity.

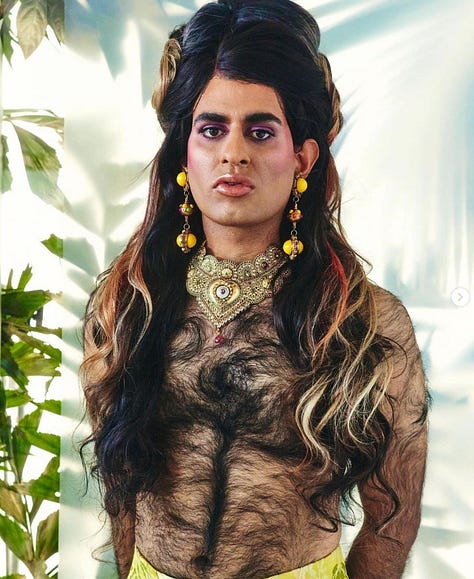

The final work I invite you to think with me on is a photographic work called Van Gogh’s Back (1995). Van Gogh’s Back (1995) feels distinctly queer to me. In the way that queer icon/poet Alok Vaid Menon fashions their own body hair. The soaped-up, sudsy quality implies this sensual act of care. What it means to wash someone, what it means to anoint them (hello, Mary Magdalen).

The texture of the hair in Van Gogh’s Back achieves brushstroke, and becomes adornment. Why don’t we worship body hair the way we fetishize head hair? Why is body hair not even more sacred? Having body hair is a beauty standard that exists way outside the western standards of beauty. At times it feels like a radical act to simply have body hair. To celebrate it is an act of justice.

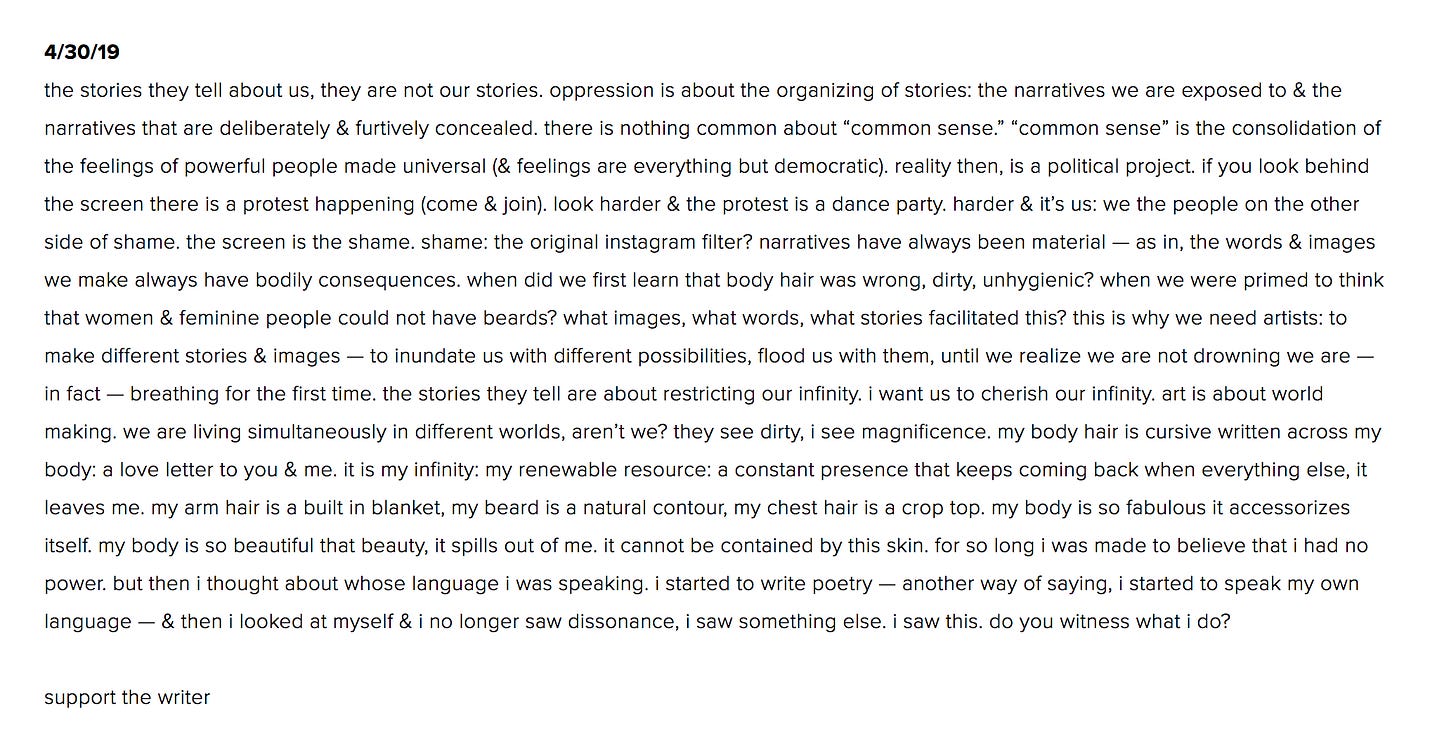

my body hair is cursive written across my body: a love letter to you & me. it is my infinity: my renewable resource: a constant presence that keeps coming back when everything else, it leaves me…the body is so fabulous it accessorizes itself.

— Alok Vaid Menon

In Hatoum’s work, hair, even in its quietest gesture—a single strand—is enough.

The phrase ‘do not harm a single hair on their head’ comes to mind.

Can a single hair even be harmed?

If the answer is yes, will it therefore necessarily harm the person attached to it? The delicacy of Mona Hatoum’s work would say yes. A single thread is enough, a single thread can tell infinite stories: of love, loss, persecution, dislocation. Coiled within each hair itself is DNA that represents a whole life. And whether the individual stands in for the whole, the individual is enough.

Protect the individual. Through the individual, we might protect the collective.

Happy Pesach everyone, may all beings be free.

xo,

Suzanne

Mona Hatoum. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/mona-hatoum-2365/who-is-mona-hatoum accessed 4/18/2024.

Using the Body Against the Body Politic: Mona Hatoum on How Art Can Be a Form of Resistance. https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/book_report/using-the-body-against-the-body-politicmona-hatoum-on-lessons-in-art-as-resistance-54354 accessed 4/17/2024.

Interior/Exterior Landscape. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hatoum-interior-exterior-landscape-t15265 accessed 4/24/2024.

That mullet is art!